« Dairy History « Mount Desert Island Dairies

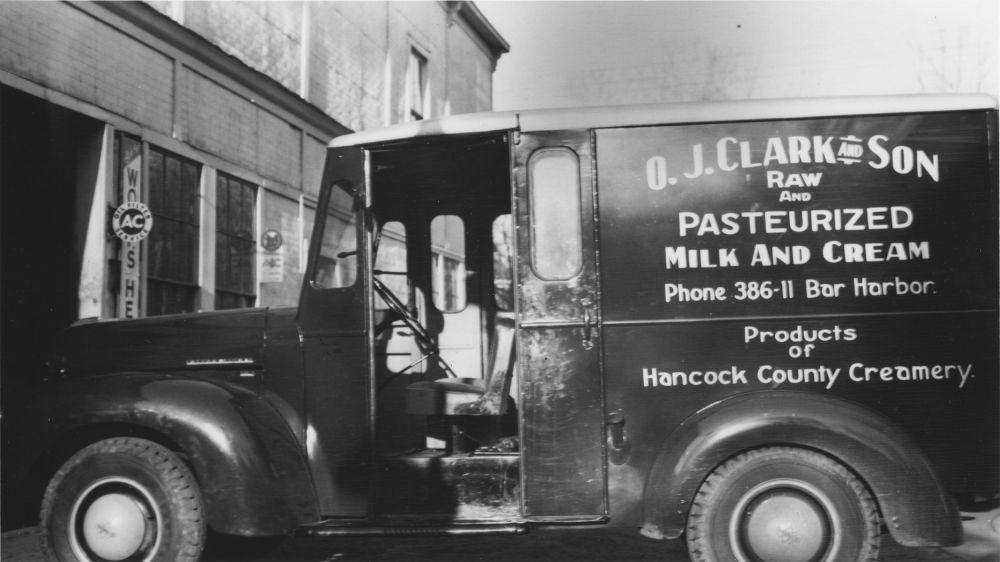

First new truck that O. J. Clark bought. The products come from Hancock County Creamery. Early on the Clarks didn't have any way to process milk.

O. J. Clark and Son

Bar Harbor

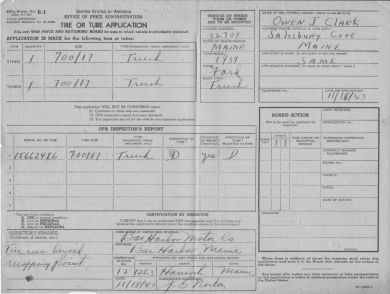

Owen J. Clark and Son and Clarks Southwest Dairy never had cows and a farm. We were a processing plant that had milk routes. In fact, I would say that O. J. didn't know anything about cows. It all started very low tech, O. J. had a wooden ice box in his garage in Salisbury Cove where he kept the milk he bought locally. In the beginning he would fill the bottles by hand. He also bought milk from N. Searle Perry from Hampden and after that Hancock County Creamery. O. J. eventually built a processing plant in Southwest Harbor in 1950.

Other Names Associated With This Dairy: Owen J. Clark, Clarks Southwest Dairy

Dairy History

Owen J. (O. J.) Clark Jr. left his job as a chauffeur for Mrs. Atwater Kent in 1937 after nine years. He was working as a mason's helper when William P. Hamilton (a wealthy summer resident and great-grandson of Alexander Hamilton), recognized him as Kent's driver and asked O.J. to be his chauffeur.

Hamilton was the owner of Thirlstane Ranch Inc., a collection of over 40 small farms in the Mount Desert Island, Trenton, and Lamoine area bought during the late 1930s from area families. Among the farms he took over were Andrews Farm and Clarence Alley’s, both of whom formerly bottled milk under their own names. Once he purchased a property, he would have the buildings repainted in the Thirlstane colors: yellow with blue trim and red-shingled roofs. In addition to dairy cows, the farms raised beef cattle, peacocks, pheasants, and thoroughbred horses.

One day Hamilton asked O.J. to drive a new milk truck with Thirlstane Ranch milk over to Southwest Harbor to hand out free (pint bottles) of milk as samples. O.J. succeeded in finding new customers for the products and was eventually put in charge of Hamilton’s milk routes, both delivering the milk and recruiting new business. Hamilton tired of farming after just a couple of years and suspended all operations. Milk was no longer produced under the Thirlstane label. But a route full of loyal customers had been built up in the meantime, offering an opportunity for entrepreneurs to step in and take over.

O.J. made an arrangement with Hugh Kelly, Thirlstane’s former bookkeeper, to split up the routes between them. Kelly delivered to the Bar Harbor customers and called his business Kelly’s Dairy. He bought milk from area farmers and processed and bottled it in a building on Norway Drive that was reportedly the first building to burn in the Bar Harbor Fire of 1947. Eventually, he bought the old Clarence Alley Farm, the site of Thirlstane’s processing plant on Crooked Road.

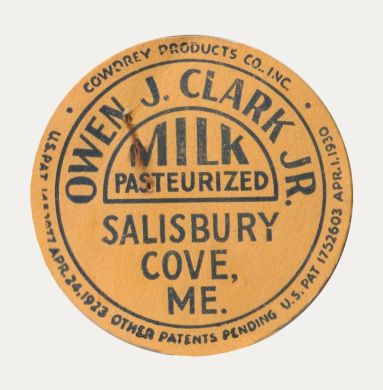

O.J. took over the Thirlstane routes in Southwest Harbor, Somesville, Town Hill, Tremont, and Salisbury Cove and called his business simply O.J. Clark Jr. His wife, Doris, kept the books. Their son John (Jack), who was 13 years old at the time, helped his father weekends and summers. Since Thirlstane’s last delivery day was March 14, O.J. started delivering milk on the Ides of March (March 15), 1939, in a blizzard. He originally bought his milk from N. Searle Perry’s farm in Hampden. Perry had been the manager of the Thirlstane Ranch milk plant.

The Perry Farm, which had the biggest barn in the state at that time though sadly it has since fallen down from disrepair. Perry produced and processed the milk, bottled it, and delivered it to O.J. in Salisbury Cove seven days a week. The only products were quarts of milk, pints of milk, and half pints of heavy cream. Every day 18 to 20 cases were delivered and put on ice into a lidded wooden cooler inside O.J.’s garage at Salisbury Cove. O.J. paid Perry eight cents a quart, then sold to stores for ten cents a quart, and to household customers for twelve cents a quart.

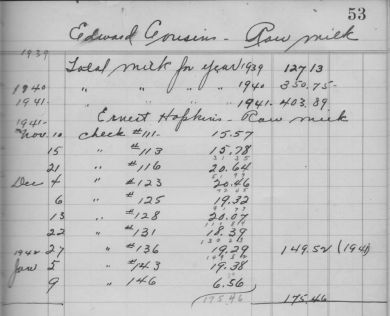

Eventually, the long trip from Hampden became impractical for Perry, and O.J. had to find another source of milk. He started buying milk from the Hancock County Creamery in Ellsworth and hauled it himself from Ellsworth to the island each day, which meant they had to get up at midnight to go to work. This arrangement lasted throughout the 1940s. Milk was delivered seven days a week, year-round. During most of the year, bottles were left on the doorstep very early in the morning. But in the winter, bottles might freeze if they sat too long outside, pushing the cream and stopper several inches in the air, eventually breaking the bottle around the bottom. So winter deliveries were made later in the morning when customers were more likely to be awake. This was before the days of insulated milk boxes.

In the summer, O.J. and Jack would get up around 2:00 a.m. to start their deliveries. They often found themselves heading over to the western side of the island at the same time as the MDI Dairies truck, driven by Don Watson. MDI Dairies was a business formed by a group of small dairy farmers including Percy Kief, Frank Andrews, Henry Sweet, Clarence Alley, George Fogg, and Wm. DeLaittre. Jack recalls that the MDI Dairies truck, like their bottles, had a large Indian head on the side, and he would run in to tell his father “Here comes the Indian”. Although they each had their own routes, Jack remembers the excitement of those early years when they would feel like they were racing their competitors over to the other side of the island, each of them always on the lookout for new customers.

In 1941, the company name was changed to O.J. Clark and Son. One compelling reason was to keep son Jack, now 15 and with a driver’s license, from going to work for Harold MacQuinn Inc., who was expanding Trenton Airport for the Navy and was hiring truck drivers. With the war came shortages, gas rationing, and cream rationing, and home deliveries were changed to three days a week, wholesale to six days. When Jack was 18, he joined the army and ended up serving in the 69th Infantry Division in Europe. He came home in 1946 and joined his father full-time.

At that time there were approximately 100 similar enterprises in Maine, mostly dealers who did not produce or process the milk but bought it already bottled and delivered it. Even with the reduced demand for raw milk, Clark’s still had a few customers that requested it. O.J. arranged to leave clean bottles with Chan Gilbert at Mountain View Farm on Crooked Road in West Eden. Gilbert would fill them with unprocessed milk and put a cap labeled “raw milk” on top, and Clark’s would pick them up to be delivered the next day.

In 1950, O.J. Clark and Son began building a processing plant on Seal Cove Road in Southwest Harbor, on land purchased from Elwell Trundy, the building built by the tobacco chewing Jasper Hutchins. The name was changed to Clark’s Southwest Dairy, Inc. so that the name would appear first in the yellow page listings under milk dealers. The processing plant had state-of-the-art equipment: a modern automatic bottling machine, and a bottle washer dubbed by the Clarks “the Cadillac” because it cost $3,500, as much as a new Cadillac at the time. Pasteurization was first done in a 200-gallon batch pasteurizer with a surface cooler, and later in a flash pasteurizer that kept the milk in a closed system.

With the new processing capabilities, business began to grow. Now Clark’s was able not only to process and bottle milk under the Clark’s Southwest Dairy label but also to put up milk for some other small dairies under their own labels. These smaller dairies had previously bottled their own raw milk, but had found that the public was now demanding pasteurized milk more. (Pasteurization not only killed harmful organisms but made milk last longer.) Rather than sell their routes, these dairies stayed in business by still using their own bottles and still delivering, but letting Clark’s do the processing and bottling. Among those farms were Bordeaux Dairy, H.C. Whitney (Fair Acres), Linscott’s Dairy, Morrison’s Dairy, and Walter Sargent (Old Homestead Dairy).

Gradually Clark’s expanded its line of products, eventually selling even some non-dairy items. Jack made buttermilk at the dairy once a week, but sour cream, yogurt, orange juice, and eggs were bought wholesale. Cottage cheese was bought in bulk from H.P. Hood and repackaged into Clark’s Dairy containers. The round milk bottles from the ‘40s gave way to the square bottles of the ‘50s, and they lasted into the early ‘60s until cartons came in.

In the late 1970s, the day of the small dairy was coming to an end, largely due to the growing popularity of large chain grocery stores. These stores drew customers away from the “mom and pop” grocery stores, which people now used only for occasional shopping. These little stores had been an important wholesale market for small dairies, whose sales then suffered as well. The chain stores were buying milk products, but only from large producers who could contract to provide huge quantities at low prices, something small dairies could not do.

Clark’s Dairy sold its routes, trucks, and some machinery to Hancock County Creamery in 1980. One of the pieces of equipment Jack sold was a bulk milk tank “space saver” to the founders of Ben and Jerry's Ice Cream. They showed up and paid for it in cash, all small bills. Jack always had the impression that they were paying for it with money from selling ice cream cones!

For years after that, there was a steady stream of milk processing plant closings and sales. For a while, after the dairy closed, Jack bottled and sold distilled spring water from a natural spring on the premises that supplied the dairy with water for all its operations. He eventually sold the property, which is now the site of Mt. Desert Spring Water. At a glance, it looks much as it did when it was a processing plant for milk.

Additional Photos

Select a photo to view larger.

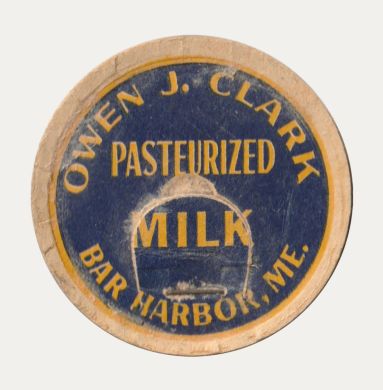

Our first bottle, used back when all we had was a wood box with ice in the garage to keep the milk cold.

Jack Clark milk truck 1946

Jack got back from the WW2 in 1946 and brought his new wife from Denmark – Rita. She posed for a shot beside this milk truck also. It must have been a big deal purchase for the O.J. Clark and Son dairy, at that time in Salisbury Cove, Bar Harbor.

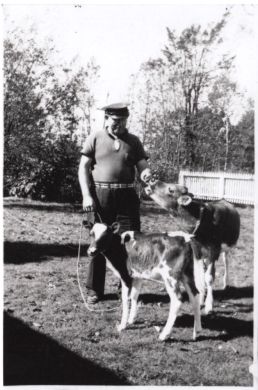

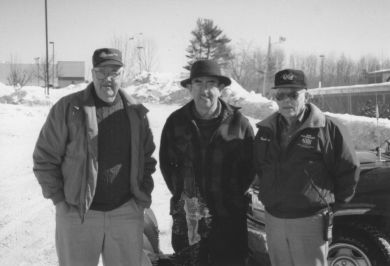

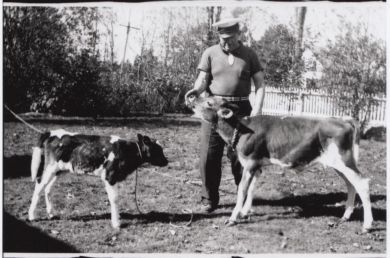

O.J. Clark with cows (photo 1 of 2)

O. J. Clark and Son and Clarks Southwest Dairy never had cows as a dairy farm would. We were a processing plant that had milk routes. I would say that O. J. didn't know anything about cows, so who knows why he is posing with them.